|

|

The History of Rancho Los Encinos

The

site that is now known as Los Encinos was a "rancheria"

(the Spanish term for an Indian village) of the tribe now called

"Fernandeño", "Gabrielino" or Tongva, for several

thousand years. In 1797, when the San Fernando Mission was completed,

the site was largely evacuated.

The

Missions did not use military force to bring Indians into the

Mission, though they would use it to keep them there once they

had converted and become "neophytes". However, the diseases

the white men brought with them, and the destruction of the local

food sources caused by the Mission cattle put the Indians in a

desperate state. A significant majority of the Indians in California

died within a few years of the arrival of the white man from a

combination of disease and starvation. While the padres had the

best of intentions and were horrified at the death they saw around

them, their arrival was the root cause of this inadvertent genocide.

|

| San Fernando Mission in the Spanish Period |

|

This

disease and starvation did have the effect of forcing most

of the Indians living anywhere near the Spanish settlements,

including those in the San Fernando Valley, to place themselves

under the Mission's protection and control.

When

the Mexican government dissolved the California missions

in 1834, three Mission Indian named Ramon, Francisco and

Roque were given a 4,460 acre rancho (1 Mexican League)

in what was to become Rancho Los Encinos. They and their

families made a marginal living grazing cattle and raising

simple crops. On July 8th, 1845, Governor Pio Pico officially

recognized their claim to the land, but by that time Francisco

and Roque were dead. Their widows inherited the land and

worked it for a few years with Ramon and his family until

1849 when Roman deserted them and his daughter Aguedo, and

ran off to the gold fields. Unable to continue, they sold

out to a Ranchero named Vincente de La Osa (or "de

La Ossa"). |

|

| Indian Vaqueros lassoing

a steer |

|

Before

California was conquered by the United States in 1847, and

the Gold Rush began in 1849, cattle ranching had been the

center of the entire "Californio" economy. The Californio

"rancheros" raised huge herds of cattle on the

vast grasslands of places like the San Fernando Valley.

The

rancheros and their vaqueros (who were almost all California

Indians) would gather the cattle once a year in a rodeo,

and then slaughter hundreds of them. There was far more

meat than they could eat, so most of the beef was left to

be eaten by the local wildlife, while the rancheros saved

the hides and tallow.

The

hides and tallow would be traded to Yankee sea captains,

who would sail around Cape Horn in ships loaded down with

fabrics, clothes, household goods, liquor and any other

items the Californios might want. The sea captains would

trade their cargo for as many hides and barrels of tallow

as their ships could hold, and then return home to sell

them. The story of one of these voyages is told in the famous

book "Two Years Before the Mast", by Richard Henry Dana.

|

The

De La Osa rancho however, opened just as this phase in California

history was coming to a close. When hundreds of thousands

of gold miners came pouring into California, there were

suddenly enough mouths to eat all the beef this fertile

land could produce, and the meat became more valuable than

the hides. Californio Rancheros like Vincente made a great

deal of money driving their cattle to the gold fields and

selling them there at inflated prices. For a few years,

the Californios prospered under the Stars and Stripes.

In

1849, Vincente De La Osa built the adobe that still stands

at Los Encinos. It is an excellent example of the basic

Californio style of adobe.

It

is long and narrow, with every room having one or more doors

connecting to the outside, and many adjacent rooms not connecting

to each other. Only in a climate as mild as Southern California,

would anyone consider designing a house that way. |

|

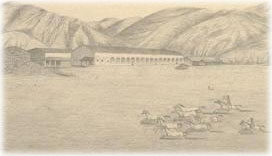

| The De

La Osa Adobe with sheep |

|

|

| Jim

& Manuela Thomson |

|

The

cattle boom did not last, and when the miners went home

or settled down, the demand for cattle declined. Vincente

compensated by establishing a small vineyard, raising some

sheep, and letting out rooms to travelers. There were many

customers, since the Rancho was located along the primary

road through California, El Camino Real, which in Encino

corresponds to Ventura Blvd. Vincente died in 1861, leaving

his widow Rita with 12 children, and pregnant with a thirteenth.

Rita

managed to hold on for six more years, until 1867 when she

conveyed the 4,460 acre rancho to her son-in-law, Sheriff

James Thomson of Los Angeles and her daughter Manuela for

$3,500. Manuela died in 1868 and the Rancho was sold to

two Frenchmen, Eugene and Phillipe Garnier.

The

Garniers were energetic builders, and added much to the

Rancho. They built a stone-lined pond, in the shape of a

Spanish guitar at the site of the spring; they built a two

story limestone building to serve as a bunkhouse and they

built a roadhouse across the road (Ventura Blvd.) which

became the focal point of the local Basque community.

They

also plunged with both feet into the Los Angeles sheep boom

of the early 1870s. Three years of drought followed by two

years of rain had combined with falling cattle prices to

wipe out the cattle economy in Los Angeles. The sheep moved

in to fill the void.

The

Garniers spent freely on prize Spanish and French Merino

breeding rams and borrowed heavily to finance the expansion

of their herds and facilities. They had the reputation for

producing the finest wool in Southern California.

|

Unfortunately,

it wasn't good enough. The Los Angeles sheep boom was built

on dreams and speculation, and the poor quality of most

of the Southern California product, combined with the expenses

of getting the product back east to the mills, made sheep

ranching on the scale of the Garniers and their many sheep

ranching neighbors, economically insupportable.

The

market collapsed in 1873, and joined with a nation wide

depression to ruin the Garniers and many like them.

They

hung on until 1878, when their primary creditor, a

Basque named Gaston Oxarart, purchased the ranch at a Sheriff's

auction. He continued to raise sheep, but like most landowners

in the Valley, he moved more and more into agriculture.

In 1886, Gaston died, and the ranch passed to his nephew

Simon Gless. In 1889, Gless sold the rancho to his father

in law, Domingo Amestoy. This was the last time the 4,460

acre ranch was sold as a whole. In the coming years, it

would slowly be taken apart, a piece at a time.

In

1916, 1,170 acres of land were sold from the Rancho. This

parcel was subdivided and became the city of Encino.

|

|

| The Garnier Building |

|

In 1949, through the efforts of Mrs. Mary Stuart in mobilizing

the local community to save the buildings from developers,

the last remaining parcel of land, containing the De La

Osa adobe, Garnier House and spring were purchased by the

State of California, and the Los Encinos State Historic

Park was created. |